The Northern Harrier of CHRP

The Northern Harrier aka the Marsh Hawk flies low by gliding over a marsh or grassland when hunting. It has an owlish face which helps to hear mice and voles beneath the vegetation. All Northern Harriers have a white rump that is visible when they fly.

The Northern Harrier is one of the a few raptors including the Red-tailed Hawk and Great horned Owl that are residents of CHRP and can be seen almost all year long at the park. They cover a very wide territory and can be seen gliding over all the marsh areas of CHRP. At times they seem to develop a fix path that they would keep following in a cycle until they catch something.

The Northern Harrier is one of the a few raptors including the Red-tailed Hawk and Great horned Owl that are residents of CHRP and can be seen almost all year long at the park. They cover a very wide territory and can be seen gliding over all the marsh areas of CHRP. At times they seem to develop a fix path that they would keep following in a cycle until they catch something.

A male Northern Harrier aka the Grey Ghost has a color of grey and white, compared to a female which is darker or predominantly brown in color. The male to female ratio is about 1:3, which is why you see females more often than males, and perhaps this is why the male can have up to 5 mates at any one time.

A male Northern Harrier aka the Grey Ghost has a color of grey and white, compared to a female which is darker or predominantly brown in color. The male to female ratio is about 1:3, which is why you see females more often than males, and perhaps this is why the male can have up to 5 mates at any one time.

And as the sole food provider for its mates and offspring, the dude stays VERY busy. Imagine if he has 3 active nesting and each one has 3 chicks, that’s 9 chicks with 3 extra mouthes to feed on top of that. Perhaps this is why the female is the only one that incubates their eggs and later take care of the offspring.

And as the sole food provider for its mates and offspring, the dude stays VERY busy. Imagine if he has 3 active nesting and each one has 3 chicks, that’s 9 chicks with 3 extra mouthes to feed on top of that. Perhaps this is why the female is the only one that incubates their eggs and later take care of the offspring.

The female, however, goes hunting and brings the food to their offspring when the male goes out without bringing food back sometimes while the chicks are constantly calling with hunger.

The female, however, goes hunting and brings the food to their offspring when the male goes out without bringing food back sometimes while the chicks are constantly calling with hunger.

When it comes to type of prey, the Northern Harrier is not a picky bunch. I have seen them bringing back jack rabbit, although not in a whole shape due to the size.

Others are snakes, cotton-tailed rabbit, lizards, possums, gophers, ducks, ducklings, and smaller birds. Often times when food is scarce, the male brings back smaller catches such as other birds’ chicks.

Others are snakes, cotton-tailed rabbit, lizards, possums, gophers, ducks, ducklings, and smaller birds. Often times when food is scarce, the male brings back smaller catches such as other birds’ chicks.

This picture is a sequence of a male harrier passing its catch in mid-air to one of its offspring during the nesting season, which we usually refer as food exchange.

This picture is a sequence of a male harrier passing its catch in mid-air to one of its offspring during the nesting season, which we usually refer as food exchange.

This ritual, which actually starts during the nesting season with the male bringing food to his mates and passing it to them in mid-air, also acts as training for the chick, so they’re ready for the adulthood after they’ve fledged.

Other raptors such as the Peregrine Falcon and White-tailed Kite perform the same ritual except they do not drop the food until grabbed by the female or chicks.

Other raptors such as the Peregrine Falcon and White-tailed Kite perform the same ritual except they do not drop the food until grabbed by the female or chicks.

You rarely see any failures of the exchange between two adult birds, but it’s a different story with the chicks, which is why the ritual is an essential part of the adulthood preparation.

You rarely see any failures of the exchange between two adult birds, but it’s a different story with the chicks, which is why the ritual is an essential part of the adulthood preparation.

During this nesting season, the act goes on for a few weeks and bird photographers from all over the Bay Area gather along the Muskrat trail, waiting for the actions to take place with one common hope: to bring home the so-called holy-grail shot!

During this nesting season, the act goes on for a few weeks and bird photographers from all over the Bay Area gather along the Muskrat trail, waiting for the actions to take place with one common hope: to bring home the so-called holy-grail shot!

There seem to be more actions taking place in the late afternoon compared to other times of the day, which works at an advantage for us photographers since lighting would be more ideal then.

Prior to that, most of the shots taken seem soft since the camera ‘sees’ a layer of haze in the air, especially when the subject is quite a distance away. By late afternoon, both the sun and wind would be behind us. The wind factor would make the harriers fly toward us , reducing the so-called ‘butt shots’.

Prior to that, most of the shots taken seem soft since the camera ‘sees’ a layer of haze in the air, especially when the subject is quite a distance away. By late afternoon, both the sun and wind would be behind us. The wind factor would make the harriers fly toward us , reducing the so-called ‘butt shots’.

Most of us would post our shots on Flickr sort of comparing who has the best shots, and usually everyone would keep going back to not only get the best shot but also the actions, poses, and preys.

Most of us would post our shots on Flickr sort of comparing who has the best shots, and usually everyone would keep going back to not only get the best shot but also the actions, poses, and preys.

Besides, once you have the shot that you’ve always wanted and you see some else has yet a different pose, you just have to have it too..

Besides, once you have the shot that you’ve always wanted and you see some else has yet a different pose, you just have to have it too..

Such motivation.. This year our keen photographer friend, Ken Phenice Jr. seems to have the best series of the Northern Harrier shots by far.

Many have asked me what it takes to capture an action sequence like this, be it a Northern Harrier, Peregrine Falcons, White-tailed Kites, or American Kestrels (all of which perform such exchange act). As with most bird photography, it’s part preparation, and part luck. Capturing good images of this act requires multiple attempts and a lot of luck since the field covers a wide area.

Many have asked me what it takes to capture an action sequence like this, be it a Northern Harrier, Peregrine Falcons, White-tailed Kites, or American Kestrels (all of which perform such exchange act). As with most bird photography, it’s part preparation, and part luck. Capturing good images of this act requires multiple attempts and a lot of luck since the field covers a wide area.

So , when the event takes place from afar you would have to wait for the next one and hopefully it would be within a good range of your lens reach.

So , when the event takes place from afar you would have to wait for the next one and hopefully it would be within a good range of your lens reach.

At Coyote Hills Regional Park, every photographer respects the birds personal space as not to violate it for the sake of good images.

At Coyote Hills Regional Park, every photographer respects the birds personal space as not to violate it for the sake of good images.

Being in the right place at the right time is not always the answer without a good preparation.

Being in the right place at the right time is not always the answer without a good preparation.

In terms of preparation, you just need to make sure that your camera settings are ready for such actions. Personally, I keep my f/stop at f/5.6 or f/6.3 when combined with a 1.4X teleconverter while f/8.0 to f/9.0 with a 2X. As for shutter speed, again my magic number seems to be 1/1600s unless better lighting permits me to push it up higher while not sacrificing high ISO.

Exposure compensation: shooting against the sky as backgound, a minimum of +1 or usually higher is needed depending on lighting condition and also if you’re shooting darker birds. You do not want to push up too high since your shots will be over exposed when the bird flies down and your background is now the vegetation and there’s not enough time to simply change the settings on the fly while tracking the bird.

Exposure compensation: shooting against the sky as backgound, a minimum of +1 or usually higher is needed depending on lighting condition and also if you’re shooting darker birds. You do not want to push up too high since your shots will be over exposed when the bird flies down and your background is now the vegetation and there’s not enough time to simply change the settings on the fly while tracking the bird.

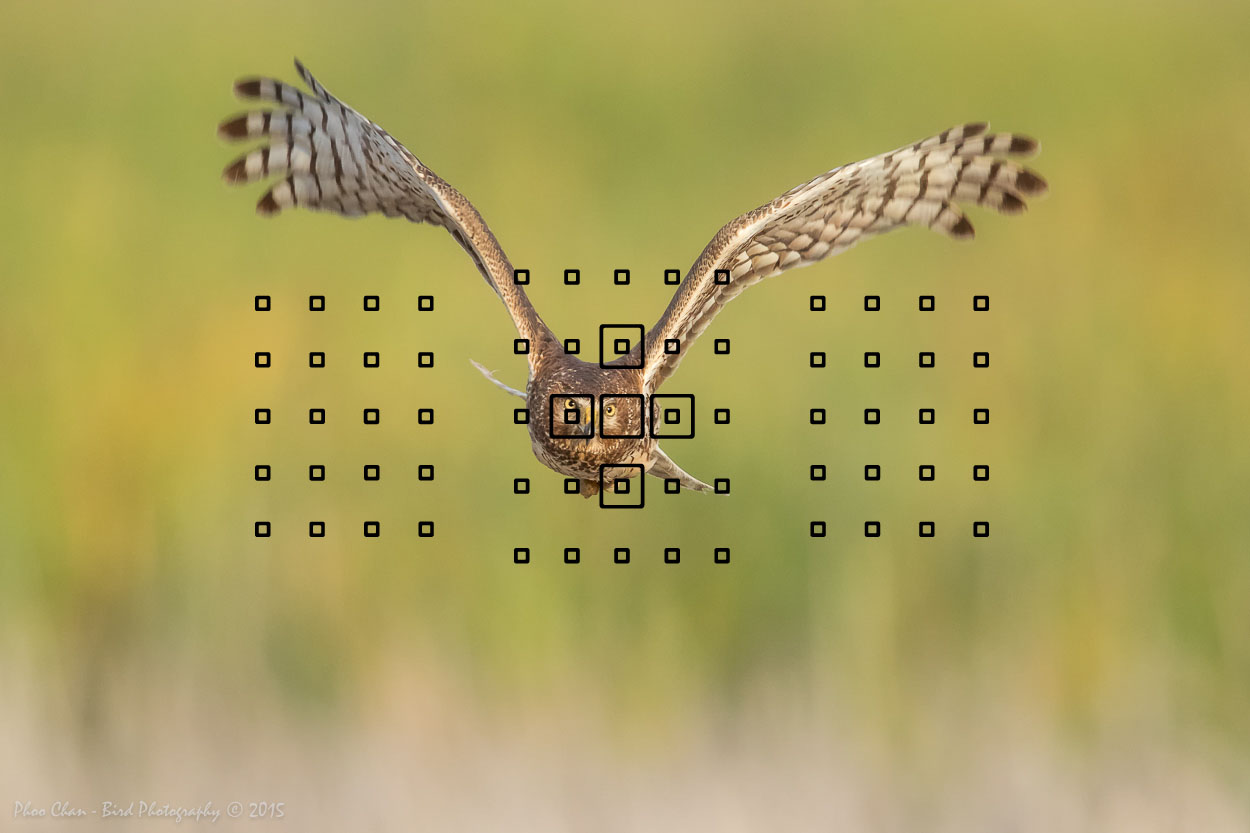

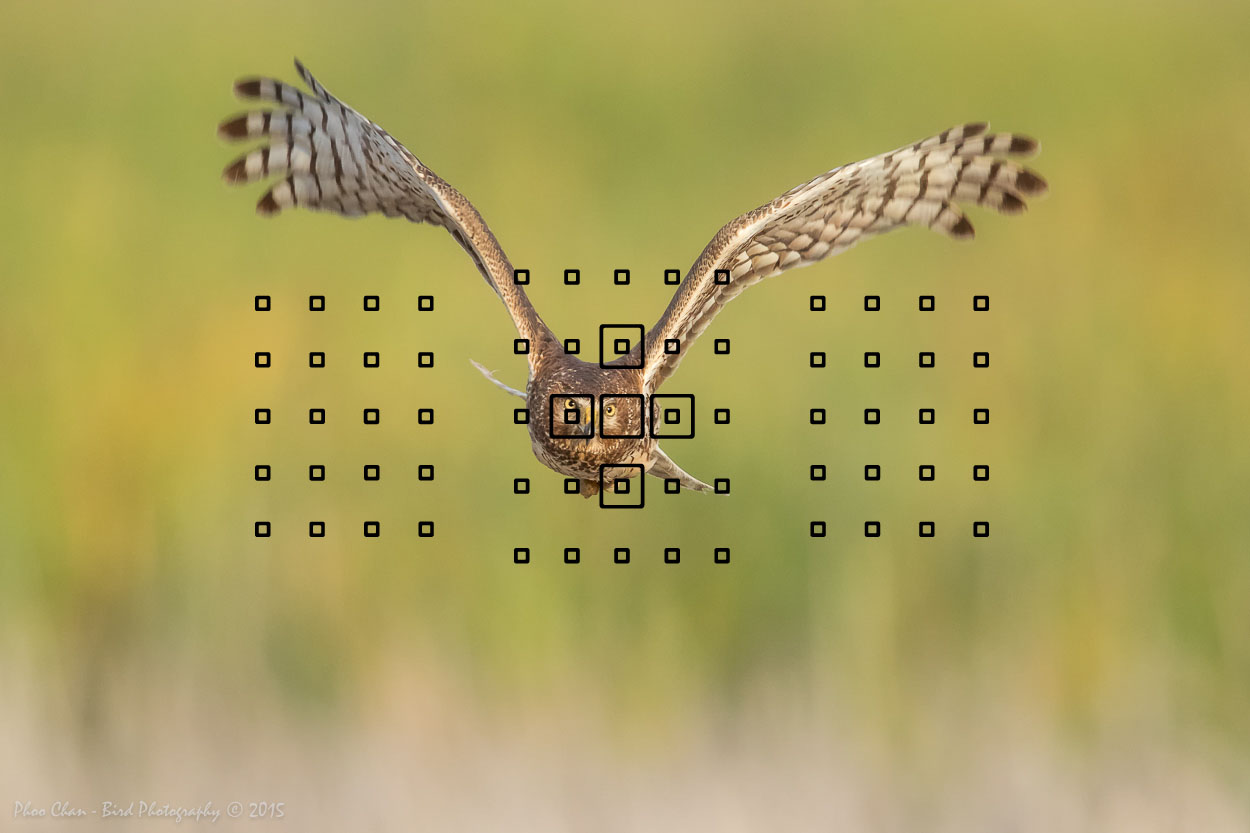

Since I shoot with Canon, my go to focusing point is usually set to the AF Point Expansion although I quickly switch to zone or sometimes the ‘ring of fire’ (all points) shooting against the sky which is a lot easier to keep the flying bird in focus compared to shooting against a busy background since the camera would pick-up the background instead of the bird when using more points.

Since I shoot with Canon, my go to focusing point is usually set to the AF Point Expansion although I quickly switch to zone or sometimes the ‘ring of fire’ (all points) shooting against the sky which is a lot easier to keep the flying bird in focus compared to shooting against a busy background since the camera would pick-up the background instead of the bird when using more points.

I find making use of the preset focus button on my EF600mm f/4L IS II is very useful especially when I’m using the 2.0X teleconverter and the focus range is set to maximum to avoid the lens, taking a longer time to lock its focus on the flying bird which is being referred as focus hunting. Usually you would miss the actions once you lose your focus while tracking the bird if you don’t quickly recover.

I find making use of the preset focus button on my EF600mm f/4L IS II is very useful especially when I’m using the 2.0X teleconverter and the focus range is set to maximum to avoid the lens, taking a longer time to lock its focus on the flying bird which is being referred as focus hunting. Usually you would miss the actions once you lose your focus while tracking the bird if you don’t quickly recover.

To minimize the lens hunting, I highly recommend using this preset focus feature by setting the distance where you want the lens to get back the preset distance once focus is lost. Setting the lens focus range limiter to the minimum focus distance to limit the full range will also reduce the lens hunting.

To minimize the lens hunting, I highly recommend using this preset focus feature by setting the distance where you want the lens to get back the preset distance once focus is lost. Setting the lens focus range limiter to the minimum focus distance to limit the full range will also reduce the lens hunting.

As for Canon Case settings, I normally customize based on case 2 which tailor to maintain focus lock instead of quick point switching, since this a slow gliding big bird that doesn’t make sudden changes too often.

As for Canon Case settings, I normally customize based on case 2 which tailor to maintain focus lock instead of quick point switching, since this a slow gliding big bird that doesn’t make sudden changes too often.

Once you have all these elements in place, just track on the male harrier when it comes back with a catch (usually you will see the female flies up in a hurry while making loud calls) and as soon as the female gets into the frame, shoot away.

Once you have all these elements in place, just track on the male harrier when it comes back with a catch (usually you will see the female flies up in a hurry while making loud calls) and as soon as the female gets into the frame, shoot away.

You do not want to pull the trigger too soon as your camera buffer gets filled up in the midst of the action resulting in missing the critical part of the actions.

You do not want to pull the trigger too soon as your camera buffer gets filled up in the midst of the action resulting in missing the critical part of the actions.